In the world of restorative and cosmetic dentistry, patients often seek solutions that require more than a single approach. While braces straighten teeth and dental implants replace missing ones, the most transformative results frequently come from the intersection of these two disciplines. For residents of Caledonia, understanding how these treatments work together is the first step toward achieving a fully functional and aesthetically flawless smile. This article explores the synergy between orthodontics and implantology, detailing the meticulous planning required to coordinate complex cases.

Introduction

A smile is a complex architectural structure. When that structure is compromised by misalignment, overcrowding, or missing teeth, the path to restoration is rarely a straight line. In Caledonia, dental professionals are increasingly seeing adult patients who require a “multidisciplinary” approach. This often involves the seamless integration of orthodontics (moving teeth) and implant dentistry (replacing teeth).

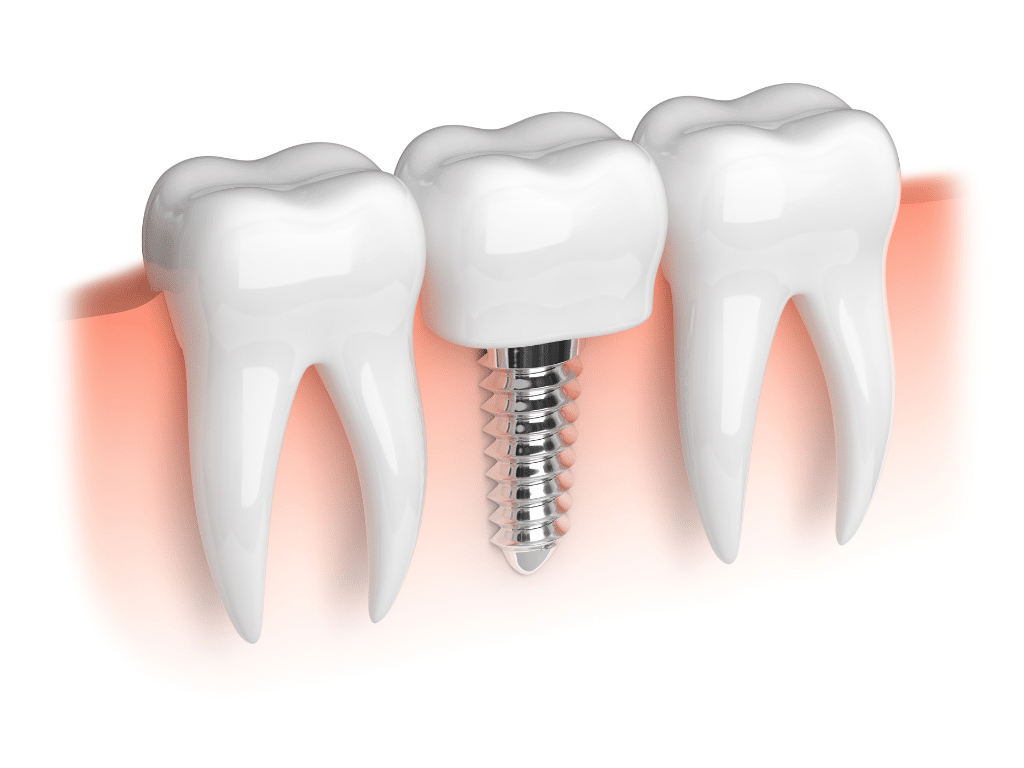

The challenge lies in the fundamental difference between natural teeth and dental implants. Natural teeth are suspended in the jawbone by ligaments, allowing them to move and shift under orthodontic pressure. Dental implants, conversely, undergo osseointegration—they fuse directly to the bone and become immovable pillars. Because of this, an implant cannot be moved once placed. This creates a critical need for strategic timing: should the braces come first, or the implant? How much space is needed? How does one manage the gap during treatment?

Coordinating care for a perfect smile requires a master plan. It is a journey that moves from digital blueprints to biological movement, and finally, to surgical restoration. By combining these therapies, patients in Caledonia can address issues that neither treatment could solve alone, such as replacing congenitally missing lateral incisors or restoring a bite collapsed by long-term tooth loss.

1. The “Ortho-First” Philosophy and Sequencing

Descriptive Paragraph In the vast majority of interdisciplinary cases, orthodontic treatment must precede the placement of dental implants. Because implants are anchored permanently into the jawbone and cannot be repositioned orthodontically, the surrounding natural teeth must be moved into their optimal positions first. This ensures that when the surgeon eventually places the implant, it is in the exact location required for the best functional and aesthetic outcome.

Detailed Information

- The Anchor Effect: If an implant is placed before the bite is corrected, it acts as an immovable anchor. If the patient later decides they want to straighten their teeth, the orthodontist cannot move the implant to match the new arch form. This can result in the implant crown looking submerged or out of alignment as the natural teeth shift around it.

- Root Positioning: It is not enough to simply have space for the crown (the visible part of the tooth). The roots of the adjacent teeth must be upright and parallel. If roots are tipped into the empty space, an implant cannot be surgically placed without damaging them. Orthodontics uprights these roots to create a safe “corridor” for the implant screw.

- Exceptions to the Rule: There are rare instances where an implant is placed before orthodontics. This is usually done when the implant is needed to serve as an anchor (see Point 3) to help pull other teeth into place, or if the tooth to be replaced is not in an area that interferes with the orthodontic movement of other teeth.

- The Caledonia Context: Local treatment plans usually involve a consultation where the restorative dentist and the orthodontic provider map out a timeline, ensuring the patient understands why there is a waiting period before the surgery occurs.

2. Managing Space for Congenitally Missing Teeth

Descriptive Paragraph One of the most common reasons for combining braces and implants is the treatment of hypodontia, or congenitally missing teeth. The most frequently missing teeth (aside from wisdom teeth) are the maxillary lateral incisors—the teeth directly next to the two front teeth. In these cases, patients often have gaps that are either too large, too small, or unevenly distributed. Orthodontics is essential to redistribute this space symmetrically before an implant can be placed.

Detailed Information

- The “Golden Proportion”: In aesthetic dentistry, the size of the lateral incisor needs to be in a specific proportion to the central incisor to look natural. Orthodontists use calipers and digital models to measure the exact millimetres of space needed to fit a crown that matches the patient’s unique tooth size ratio.

- Canine Substitution vs. Implantation: Sometimes, the plan might involve closing the space entirely by moving the canine teeth forward (canine substitution). However, if the shape of the canine is too sharp or the bite doesn’t allow it, opening the space for an implant is the preferred route. This decision is made early in the planning phase.

- Midline Correction: When a tooth is missing on one side, the entire set of teeth often drifts toward the gap, causing the centre of the smile (the midline) to be off-centre. Braces or aligners correct this asymmetry, ensuring the smile is centred on the face before the implant fills the void.

- Temporary Aesthetics: A major concern for patients is having a visible gap during treatment. In Caledonia practices, temporary solutions—such as a “pontic” (fake tooth) built into the aligner or attached to the archwire—are used so the patient never has to walk around with a missing tooth during the months of orthodontic movement.

3. Using Implants for Orthodontic Anchorage (TADs)

Descriptive Paragraph While traditional dental implants replace roots, a variation of implant technology helps facilitate tooth movement itself. These are known as Temporary Anchorage Devices (TADs) or mini-implants. Sometimes, standard restorative implants are also used for this purpose. In difficult cases where teeth need to be moved significantly, natural teeth may not provide enough stability to pull against. Implants provide absolute anchorage, allowing orthodontists to perform complex movements that were previously impossible.

Detailed Information

- Newton’s Third Law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. If braces pull a back tooth forward using a front tooth as an anchor, the front tooth will inevitably move backward. If that backward movement is undesirable, an implant (which doesn’t move) provides a solid post to pull against without unintentional side effects.

- Intrusion and Extrusion: Implants provide the leverage needed to push over-erupted teeth back into the bone (intrusion) or pull impacted teeth down (extrusion). This is particularly useful in adults with collapsed bites due to long-term tooth loss.

- Dual-Purpose Implants: occasionally, a permanent restorative implant is placed early in the treatment specifically to be used as an anchor for braces, and then later capped with a crown to function as a tooth. This requires extreme precision, as the final position of the implant must be perfect for the future crown.

- Minimizing Headgear: In the past, difficult movements required bulky external headgear. The use of implant anchorage allows for streamlined, intra-oral mechanics, making the experience much more comfortable and discreet for the patient.

4. Bone Preservation and Site Development

Descriptive Paragraph The relationship between tooth movement and bone volume is critical. When a tooth is lost, the alveolar bone begins to resorb (melt away) due to lack of stimulation. However, moving a natural tooth into an area of bone deficiency can actually generate new bone—a process called orthodontic site development. Conversely, placing an implant preserves the bone that is currently there. Coordinating these biological responses is a key aspect of the treatment plan.

Detailed Information

- The “Drifting” Technique: If a patient has a thin ridge of bone where an implant is needed, the orthodontist can sometimes move an adjacent natural tooth into that space. As the tooth moves, it carries its supporting bone with it. Once the bone has been deposited, the tooth is moved back, leaving behind a robust site for the implant. This can sometimes negate the need for painful bone grafting surgeries.

- Timing the Extraction: If a patient has a failing baby tooth or a damaged permanent tooth that needs extraction and replacement, the timing is vital. If the tooth is extracted too early, the bone will shrink before the braces are finished. Often, the extraction is delayed until the orthodontics are nearly complete so the implant can be placed immediately, preserving the socket.

- Vertical Bone Height: Restoring vertical bone loss is one of the hardest challenges in dentistry. Orthodontic eruption (pulling a tooth down slowly) can bring the bone and gum line down with it, leveling the aesthetic defects before the tooth is removed and replaced by an implant.

- Osseointegration Timeline: Once the implant is placed, it typically requires 3 to 6 months to fuse with the bone. Orthodontic retention (retainers) must be strictly maintained during this healing phase to ensure the space doesn’t close up while the bone is healing.

5. Soft Tissue Architecture and Gum Aesthetics

Descriptive Paragraph A perfect smile is not just about white teeth; it is also about the pink frame—the gums. The interface between a dental implant and the gum tissue (gingiva) is notoriously difficult to manage. Orthodontics plays a pivotal role in managing the soft tissue papilla (the triangle of gum between teeth). By aligning the roots properly and managing the space, the orthodontist prepares the “canvas” for the implant surgeon to create a natural-looking emergence profile.

Detailed Information

- The Black Triangle Dilemma: If roots are angled away from each other, the contact point between the crowns moves higher, often resulting in a “black triangle” or dark space near the gum line. Orthodontics creates parallel roots to lower the contact point, squeezing the papilla and eliminating these dark spaces.

- Gingival Levelling: Patients often have uneven gum lines. Before an implant is placed in the “aesthetic zone” (the front teeth), braces are used to intrude or extrude teeth so that the gum margins of the implant crown will match the adjacent natural teeth perfectly.

- Emergence Profile: A natural tooth emerges from the gum with a specific curvature. An implant is circular. The transition from the circular implant to the anatomical crown requires ample gum thickness. Orthodontists ensure there is enough space not just for the implant, but for the gum tissue to drape naturally around it.

- Periodontal Health: Orthodontic appliances can trap plaque, leading to gum inflammation. In Caledonia clinics, hygiene is emphasized during the pre-implant phase because placing an implant into inflamed, bleeding gums significantly increases the risk of peri-implantitis (implant failure).

6. Clear Aligners vs. Traditional Braces in Hybrid Cases

Descriptive Paragraph With the rise of clear aligner therapy (such as Invisalign), the logistics of coordinating implants have changed. Aligners offer distinct advantages and some challenges compared to traditional brackets and wires. For patients in Caledonia opting for a more discreet orthodontic route, specific protocols are used to ensure the aligners accommodate the future implant site.

Detailed Information

- Pontic Integration: Clear aligners are excellent for implant cases because a “pontic” (a tooth-shaped reservoir of composite or paint) can be fabricated directly into the aligner trays. This masks the missing tooth gap continuously, which is much more difficult to achieve aesthetically with traditional metal braces.

- Control of Root Movement: While aligners are fantastic for tipping crowns, traditional braces are sometimes superior for complex root paralleling (bodily movement). However, modern aligner attachments have improved significantly. The choice depends on how much the roots adjacent to the gap need to be uprighted.

- surgical Guides: Aligner scans can be superimposed over CT scans to create surgical guides. This allows the dentist to plan the implant placement based on the final projected position of the teeth in the aligner software, rather than their current position.

- Post-Surgery Ease: After the implant surgery, the patient may have sutures or a healing cap. Clear aligners can be trimmed back to avoid rubbing on the surgical site, whereas metal wires might irritate the healing tissue.

7. Trauma and Accident Reconstruction

Descriptive Paragraph Unfortunate accidents—whether from hockey, cycling, or slips on icy Caledonia sidewalks—often result in the loss of front teeth combined with the displacement of neighbours. These trauma cases are among the most complex. They require immediate stabilization, followed by orthodontics to reposition displaced teeth, and finally implants to replace avulsed (knocked-out) teeth.

Detailed Information

- The Triage Phase: In trauma cases, the immediate priority is saving what remains. This involves splinting loose teeth. Once healed, the orthodontist assesses which teeth have fused to the bone (ankylosis) and which can be moved. Ankylosed teeth act like implants—they don’t move. This changes the entire treatment mechanics.

- Resorption Risks: Teeth that have suffered trauma are at higher risk of root resorption (shortening of roots) during orthodontic movement. The treatment must be slower and monitored with more frequent X-rays.

- Age Considerations: If a child or teenager loses a permanent tooth in an accident, they cannot receive an implant until their jaw stops growing (usually late teens or early 20s). Orthodontics is used to maintain the space and bone volume for years until the patient is old enough for the implant surgery.

- Restoring the Bite: Trauma often breaks the “anterior guidance” (how front teeth touch). Orthodontics must rebuild this functional protection before the implant is loaded, otherwise, the forces of chewing could break the new implant crown.

8. Digital Workflow and Virtual Planning

Descriptive Paragraph The coordination between the orthodontist and the implant dentist is no longer done via paper referrals alone; it is driven by advanced digital technology. In Caledonia’s modern dental practices, the use of Cone Beam CT (CBCT) scans and intraoral digital scanners allows for a “virtual patient” to be created. This technology permits the team to simulate the entire treatment—braces and surgery—before a single bracket is placed.

Detailed Information

- Superimposition: Dentists can overlay the file of the jawbone (DICOM data) with the file of the teeth (STL data). This reveals exactly where the roots are in relation to the available bone volume, preventing the “guessing game” regarding whether an implant will fit.

- Backward Planning: The treatment is planned in reverse. The final tooth position is designed digitally first. Then, the implant position is determined to support that tooth. Finally, the orthodontic movements are calculated to facilitate that implant position.

- Communication: Digital setups allow the restorative dentist to send a digital note to the orthodontist showing exactly 7.5mm of space is needed. The orthodontist programs the wires or aligners to stop exactly at 7.5mm. This reduces treatment time and errors.

- Patient Visualization: This technology allows patients to see a rendering of their final smile on a screen during the consultation phase, helping them understand the value of the investment and the necessity of the multi-step process.

9. The Factor of Age: Adult Orthodontics and Implants

Descriptive Paragraph The demographic for this combined treatment is largely adult. Adults present unique challenges compared to adolescents: their cell turnover is slower, their bones are denser, and they often have a history of other dental work (fillings, crowns, root canals). Coordinating implants and orthodontics for adults in Caledonia requires a pace and approach that respects the biology of the mature jaw.

Detailed Information

- Slower Movement: Because adult bone is less pliable, orthodontic movement takes longer. Patients awaiting implants must be patient, as rushing the movement can lead to periodontal damage.

- Occlusal Collapse: Many adults have missing back teeth, which causes their bite to collapse and the front teeth to flare out. This is called “pathologic migration.” Orthodontics retracts these flared teeth and opens the bite, creating the necessary clearance for posterior implants to rebuild the support structure of the face.

- Fixed Bridges: Adults often have old dental bridges. These bridges connect teeth, preventing independent movement. The orthodontist often has to section (cut) the bridge to move the supporting teeth individually, with the plan to replace the bridge with independent implants later.

- Systemic Health: Adults are more likely to have conditions like diabetes or take medications (like bisphosphonates) that affect bone healing. These factors heavily influence the timing of both the orthodontic force application and the implant surgery.

10. Retention and Long-Term Stability

Descriptive Paragraph The conclusion of active treatment—when the braces come off and the implant crown is cemented—is not the end of the journey. The final critical phase is retention. Because natural teeth have a lifelong tendency to shift toward the midline (mesial drift), and implants do not move, the relationship between the two must be secured permanently to prevent the development of new gaps or food traps.

Detailed Information

- The Immovable Object: As the face matures, natural teeth continue to undergo minor eruptions and shifts. Implants do not. Over 10 or 20 years, an implant can appear to “sink” as the adjacent teeth erupt around it. Long-term retention helps mitigate this.

- Retainer Design: Standard wire retainers (Hawley) or clear retainers (Essix) must be fitted carefully around the implant crown. Sometimes, a permanent “bonded” wire is glued behind the front teeth to lock the natural teeth in place relative to the implant.

- Regular Monitoring: Patients with this dual treatment need to be monitored not just for hygiene, but for occlusal forces. If the natural teeth wear down but the porcelain implant crown does not, it can result in heavy bite forces on the implant, which can damage the bone. Regular adjustments are vital.

- The Caledonia Lifestyle: For the active community in Caledonia, protective sports guards are essential post-treatment. A blow to the face can damage natural teeth, but an implant is fused to the bone; significant trauma can fracture the bone itself. Custom guards are mandatory for retention and protection.

Conclusion

The decision to undergo a treatment plan involving both orthodontics and dental implants is a significant commitment of time, finances, and patience. It is a journey that transforms not just the aesthetics of a smile, but the functional harmony of the entire masticatory system. For the residents of Caledonia, this interdisciplinary approach offers a solution to complex dental problems that were once thought untreatable.

By coordinating the precise movement of orthodontics with the surgical stability of implants, dental professionals can rebuild smiles from the foundation up. Whether it is managing the space for a missing lateral incisor, uprighting tilted molars to make room for a new tooth, or reconstructing a smile after trauma, the synergy of these two disciplines ensures that the final result is greater than the sum of its parts. It creates a smile that is not only beautiful to look at but engineered to last a lifetime.

Ready to Transform Your Smile?

Precision Planning for Your Forever Smile.

Achieving the perfect balance between straight teeth and functional restoration requires a team that understands the big picture. If you are considering braces, aligners, or implants, let us help you map out the journey to your ideal smile.

- Name: Dentistry AT The Plex

- Address: 370 Argyle St S, Caledonia, ON N3W 2N2

- Phone: 289.960.0730

- Email: Send an email to [email protected]

- Website: Visit their website at www.dentistryattheplex.com.